Chen Nong’s Work

bu Lily Hope Chumley

Chen Nong paints standing over a table in his coffeeshop, a giant photograph draped over the table, a pallette of inks, a single battered calligraphy brush, a rag and an ashtray perched beside him. He lays a wash of color and wipes it dry, pauses to chat, mixes a new color, draws a shape in the blank spaces of the photograph, and wipes it away. He swiftly, casually builds the layered shades that define his work, finishing a painting in only a few hours.

Each photographic series is carefully planned over the course of several months. It starts with an idea, a place or an object: clay tomb soldiers; opera costumes, guns and lotus leaves; sand dunes; the moon. For weeks before the shoot, Chen Nong paints paper costumes using the same brush and pallette he uses the paint the photographs-the same quick loose brushstrokes, and the same rich greens, reds, blues and yellows, colors that dissapear in but give depth to the black-and-white prints.

Every shoot is a journey out of Beijing, a group of friends serving as models and assistants carrying costumes and props, as Chen Nong searches for the perfect location. He has already sketched several frames on paper, but he quickly designs new frames to fit the context. As a photographer-and as a painter-he is decisive. During the shoot, most of the time is spent positioning the models and arranging props and costumes: once the picture has been realized, he takes only a handful of shots.

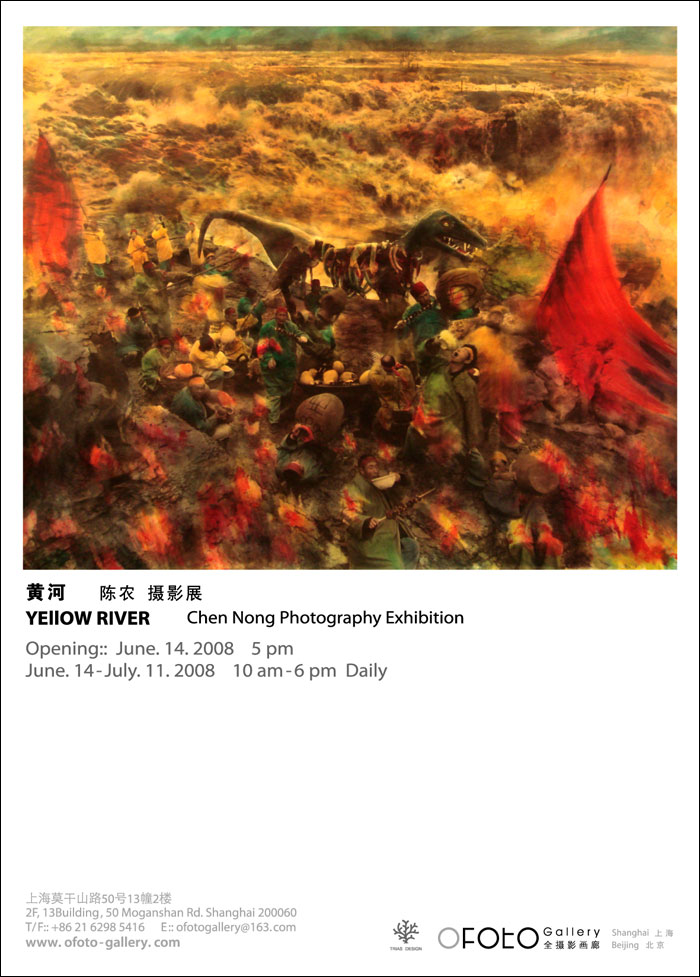

Contemporary Chinese visual culture is full of historical reenactments-recreations of moments, periods, eras-ranging from obsessively realistic epic films produced with massive budgets and loaded with visual detail, to cheap television dramas with costumes bought off-the-rack in department stores. Any time you turn on the television you see one of countless depictions of Shanghai in the thirties, all natty suits and qipaos; change the channel and you are in the 1960s, a world of padded green suits and streets without cars; change the channel again and you are in the Qing dynasty: a palace drama, or a martial-arts sitcom. Chen Nong’s work echoes this distinctively Chinese visual culture, and even its mode of production. Like a one-man set-design department, he makes his own props and costumes, relying on reference photographs and his own imagination (on a recent photoshoot, villagers walking by wondered aloud if he was shooting a television program). But Chen Nong twists the genre of historical reenactment, creating a unique pictorial language.

Many of Chen Nong’s photographs play with Chinese historical iconography-tomb soldiers stand on the moon with an astronaut, the earth visible in the background (a reference to the future, perhaps, given China’s plans for moon travel in the next decades); Chinese opera characters stand in a traditional wooden boat, carrying rifles with bayonets (calling to mind the war of resistance against the Japanese); characters in Qing costumes sit in front of the Palace Museum, real guards in caps and suits visible in the distance; young people in contemporary street clothes, with giant animal heads, play in old grey hutongs. But though his work is playful, Chen Nong’s photographs are not merely iconographic jokes or historical puns. The first thing the viewer notices is not the historical juxtaposition (i.e., opera costumes and AK47s), but the mood, most often of nostalgia or melancholy-the pensive gazes and hazy skies that belie the absurdity of the image.

Chen Nong’s pictures sometimes bring to mind the staging and expressions of early glass-plate photography. The subjects are posed as if in action, but trying not to move; faces stiff or thoughtful; eyes unfocused, gazing at the camera or into the distance. The rigid poses, dark shadows, and painted-on-colors that make Chen Nong’s pictures reminiscent of early photographs also give them the quality of half-remembered dreams, cobbled together from the images that surround and permeate us. Like dreams, these pictures have a strange kind of integrity, an integrity which comes directly from Chen Nong’s process-the link between the easy, gestural style with which he paints the costumes, and applies layers of color to the finished photograph.

Chen Nong builds layers of illusion and reality by painting his costumes, finding his locations, arranging his models, shooting and printing his photographs and coloring his prints. Unlike early twentieth century portrait photography, in which the backgrounds were painted paper and the costumes were real, Chen Nong takes paper clothes to real places. But when the photographs are printed and colored, it is hard to distinguish the paper costumes from the real surroundings, to tell the painted surfaces in the photograph from the painted surfaces on the photograph. Roland Barthes describes “the punctum” of the photograph, the tiny detail of the photograph which hooks the viewer. For Barthes, this is always something real, an index of the unique historical moment of the picture-an old shoe, a gesture of the hand. In Chen Nong’s pictures, it is not the real things which stick out, but the paper costumes-their flatness, the way they fall just short of a convincing illusion. It is the contrast between the the heavy shadows of the photograph and the light washes of color, the stillness of the models and the fleeting brushstrokes, which gives Chen Nong’s works such a haunting beauty.

Translation: Sun Rongfang

翻译:孙蓉芳