“I seem to see

The tears inside the stone

As if my eyes were gazing beneath the earth”

- Robert Bly

Annals of the Rocks

by Chen Haiyan

This time Luo Yongjin pointed his camera to Songshan Mountain. Spending years in Songshan area, he continued his unique expression with large sized photos.

The lofty ranges of Songshan and its 3.6 billion years of geological history bring about a distinctive atmosphere to this “Central Mountain (天中山, tian zhong shan, as written by famous calligrapher Yan Zhenqing and inscribed on a tablet in front of Huishan Temple).” According to historical records, 36 emperors have come to pray for the well-being of the country. Now visitors come in awe of the mighty nature. The customs and culture in this area have attracted many artists like Luo Yongjin to settle down for art creation. From time to time, he would seek chances to stay in a humble house at the foot of the mountain and wander the mountains around with his camera. Eventually the idea of making “annals" for Songshan conjured up to his mind.

The bird's-eye view of Songshan shows 72 peaks inextricably heaped up in this area woven up by more than 20 trialers routes. Luo Yongjin decided to explore every one of them so as to find out his personal way of expressing Songshan in his mind’s eye. This exhibition is only a summary for the current stage of an ongoing photography project.

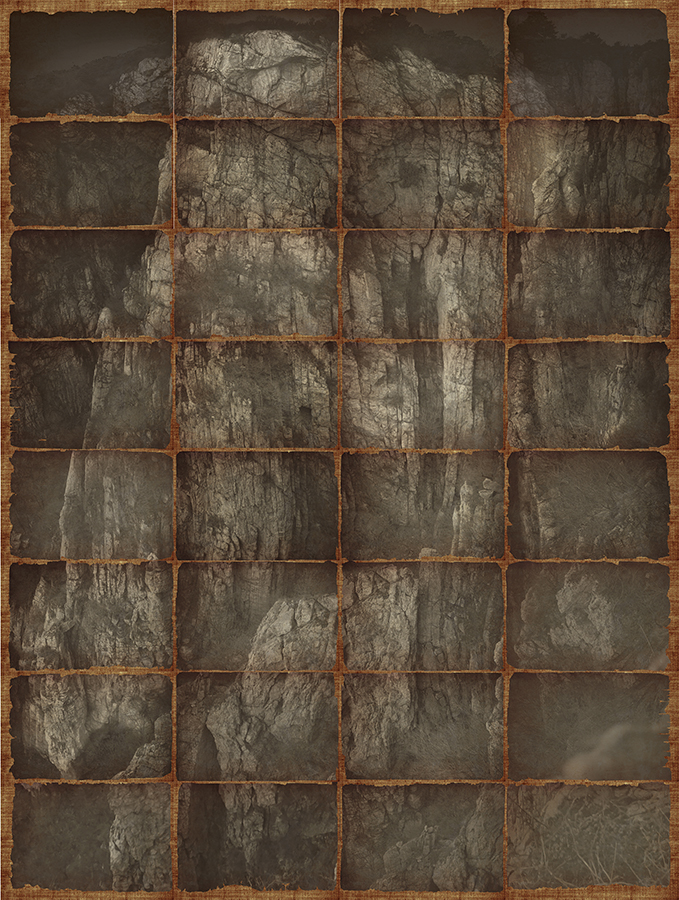

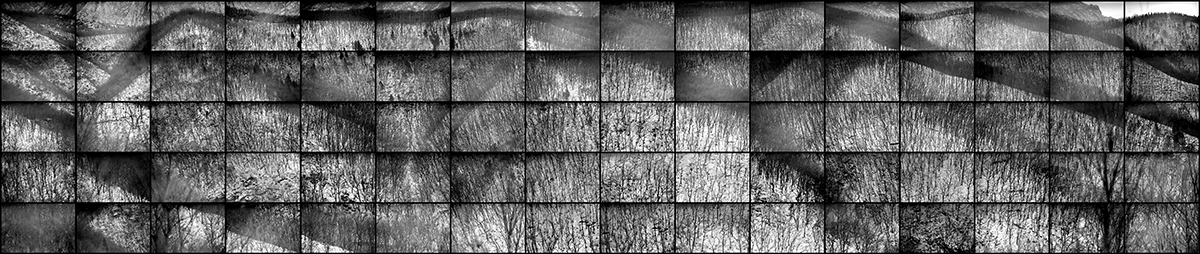

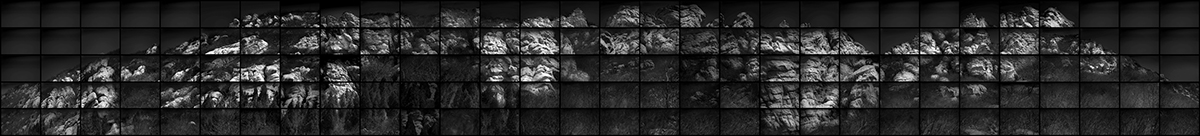

The four pieces on view are all of the mountain rocks. Each forms an “article” through partial deconstruction and overall reconstruction. They are similar but different: some forms surfaces with lines, some brings out white rocks from grey blocks, some imitates the effects of ancient book leaves, and some flashes the rocks from dark backdrop. In conclusion, Luo by picking out and emphasizing the characteristics of the rocks, tries to blur the boundaries of fiction and reality. As a senior photographer, Luo Yongjin has the insight and techniques to handle both the grand and the small with his unique style. His visual annals explore and identify the nexus of the mountains, distinguishing and stepping between the suttle gaps of recording and recreating and taking a photo and making a photo.

The swift spreading of photography has overwhelmed, in number and speed, all other art forms. The prosperity of contemporary art also pusseled our ways of looking at photography. “Ultimately - or at the limit - in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes. The necessary condition for an image is sight,” Janouch told Kafka; and Kafka smiled and replied: “We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds. My stories are a way of shutting my eyes.” In this way, Kafka avoids and prevents interpretation hijacking artworks or making the artist and artworks the dependents and tools of interpretation.

Here I’d like to mention the aesthetics of fracture (and sorry for bringing up this big term). Fracture here refers not only to the form and techniques of photo collage as exemplified in Swedish photographer O. G. Rejlander (1813-1875)’s influential work of “The Two Ways of Life”. It also refers to the fact that seeing the photos with physical eyes only is not enough any more. With fractured time and space, we are no longer satisfied with receiving from the photos the punctum and the studium (terms Roland Barthes used in Camera Lucida). Fracture is everywhere in our daily life and spiritual life. In an age where everyone is a “photographer” and “artist”, we somehow get bigger appetite for photography and artworks. It’s curious that our physical and mental hunger has never been fractured at all. The French writer Maurice Blanchot once wrote, “The essence of the image is to be altogether outside, without intimacy, and yet more inaccessible and mysterious than, the thought of the inner-most being; without signification, yet summoning up the depth of any possible meaning; unrevealed yet manifest, having that absence-as-presence which constitutes the lure and the fascination of the Sirens.” If the songs come from the little mermaid in Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, then it’s fine. What if it comes from the evil Sirens in ancient Greek myths?

Now for me, it doesn’t matter much what “language” expression is or where the songs come from. Here I’d like to quote the phrase Milan Kundera used in his short novel: “The Festival of Insignificance” to define this exhibition: Although Luo Yongjin is using photographic language to make annals for the rocks, we could celebrate the insignificance by viewing. After all, the rocks in Songshan are always silent.