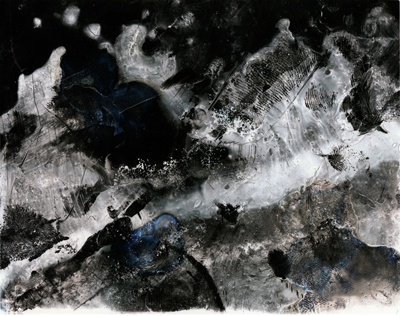

by Hong Lei

A photograph, according to Giorgio Agamben, captures the “judgement day”, a moment of eternity. He explains: “The photo can show any face, any object, or any event whatever.” Then he gave an account of a photograph named “Boulevard du Temple” by Louis Daguerre: “...at a busy moment in the middle of the day. The boulevard should be crowded with people and carriages, and yet, because the cameras of the period required an extremely long exposure time, absolutely nothing of this moving mass is visible. Nothing, that is, except a small black silhouette on the sidewalk in the lower left-hand corner of the photograph. A man stopped to have his shoes shined, and must have stood still for quite a while, with his leg slightly raised to place his foot on the shoeshiner’s stool.” From this story he concludes that photographers are angels of judgement. They pick out some people, capture moments of their lives, and endow them with eternal life. “In the supreme instant, man, each man, is given over forever to his smallest, most everyday gesture.”

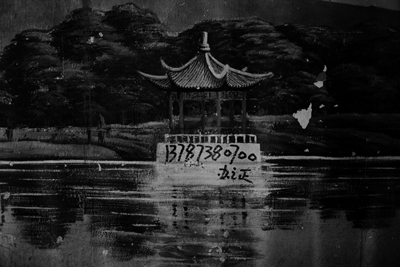

Photographers, however, cannot agree upon the standards for a “supreme instant.” Nan Goldin says: “[paraphrased by translator] What I want to figure out through my photographs is what actual experiences are like in daily life, including a sex life.” Therefore, she takes photography in order to “let others know [her] own life.” Unlike her, Martin Parr is dedicated to secretly snapping what he has subjectively observed, “With photography, I like to create fiction out of reality. I try and do this by taking society's natural prejudice and giving this a twist.” Just as stubbornly, Feng Li states, “Photography is a witness of what I see and what I therefore question, which are materialized in a flash.” “Secretly snapping” “in a flash” is kind of indecent paranoia. Although Wang Peng uses the same techniques as these photographers, he is more concerned about his own anxieties: “Photography has always been cursing, predicting, imagining and liberating things. When you turn the memories in your head into images, you make your past experience into your current works. Those fragments that didn’t matter at the moment piece together your entire life.” Finally, Robert Frank raised his doubt: “[paraphrased by translator] I wonder exactly what kind of photography tires me out.”

André Kertész tries to “write with light”. In 1912 he graduated from school and bought a camera. He keeps memos with this camera and records things around him: human behaviors, animals, his home, shadows, namely details in life and moments that enlighten him. His purpose was to "give a reason to everything around” him. This is poetic. In contrast, Zhang Huawei wants to “express my free spirit with my own eyes.” Probably as anxious as Wang Peng, I can understand how “writing with light” physically works, but to me, “expressing one's free spirit with one's own eyes” can only be seen as nihilism. Zhang also says, “Photography is my fate, and cameras are merely tools to take down what I thought aloud about the world.” Maybe what he means by his “free spirit” is his fate to think aloud? Ye Ming says, “Photography is my mind’s eye that brings the world its original colors.” Everyone has his own idea about what the world originally looked like. Julia Margaret Cameron in Victorian times said that “I longed to arrest all the beauty that came before me and at length the longing has been satisfied.” Therefore, she saw the world as sort of blurry, while Ye Ming captures excruciating details about the world.

“Writing with light” is probably a kind of poetic writing. Zhang Dapeng confirms that “on empty paper light and particles have infinite possibilities for poetry and melodies”. Wu Xiaojun pushed this point further, “Photography is a mark in time as well as an exposure in the dark.” To describe photography in such poetic ways is no doubt to give a proud name to their own work.

Jeff Wall states that “art... is, in a very major way, about making pictures or images. But that doesn’t make photography a more appropriate medium for our times, in my view.” Now that photography has become a medium, whether its content is appropriate no longer matters the most. Does this sound like what Zhang Huawei is thinking aloud? Wu Jiaying says in her quiet and tender voice, “photography, for me, is a way to approach myself.” In her case, self-expression justifies the proliferating image creation in the contemporary world. Another woman photographer, Jin Quan, says that, “Photography, for me, is a way to perceive myself and the world. I’m not interested in simply recording things or showing suffering.” She refuses grand narratives and melancholies. All she wants to do is to take good care of her own feelings. Just as Cindy Sherman puts it, "I want that choked-up feeling in your throat which maybe comes from despair or teary-eyed sentimentality: conveying intangible emotions.” Self-expression doesn’t need to be appropriate. Su Sheng says, “Photography for me is a way to perfect myself and experience life.” So maybe photography can also be a way to keep in touch with one’s spiritual side?

Hiroshi Sugimoto explains his photography like this: “[paraphrased by translator] As for my seascapes, they are without doubt closely related to religions and different from photography of daily life. Through these series, I still want to explore the origins of consciousness.” He thinks he is attempting to explore human psychology, mind, science, and religion, and he is convinced that all these are of the same origin. When there is philosophic thinking involved in photography, photos no longer play the role of what Agamben deems as the “judgement day”. Such complexity and uncertainty deprived photography of its simplicity. Therefore Tieying says, “Photography is the mirror of reality. It obsessively records the ephemeral moments of truth. The essence of photography, as far as I understand it, is perfect fantasy. It presents evidence of existence for everything and allows infinite possibility to viewers.” However, I would rather side with Roland Barthes in his doubts: “I wanted to learn at all costs what Photography was ‘in itself’: by what essential feature it was to be distinguished from the community of images. Such a desire really meant that beyond the evidence provided by technology and usage, and despite its tremendous contemporary expansion. I wasn't sure that Photography existed, that it had a ‘genius’ of its own.”

Translation: Chen Dan

翻译(中-英): 陈丹

(Note: Please respect the copyright of the original author. Thank you.)

Feng Li

Jin Quan

Su Sheng

Tie Ying

Wang Peng

Wu Jiaying

Wu Xiaojun

Ye Ming

Zhang Dapeng

Zhang Huawei